By: Dr. Al-Azharri Siddiq Kamunri

Lately, discourses on “Bangsa Malaysia” have become more frequent. So, why don’t we join in the discussion as well.

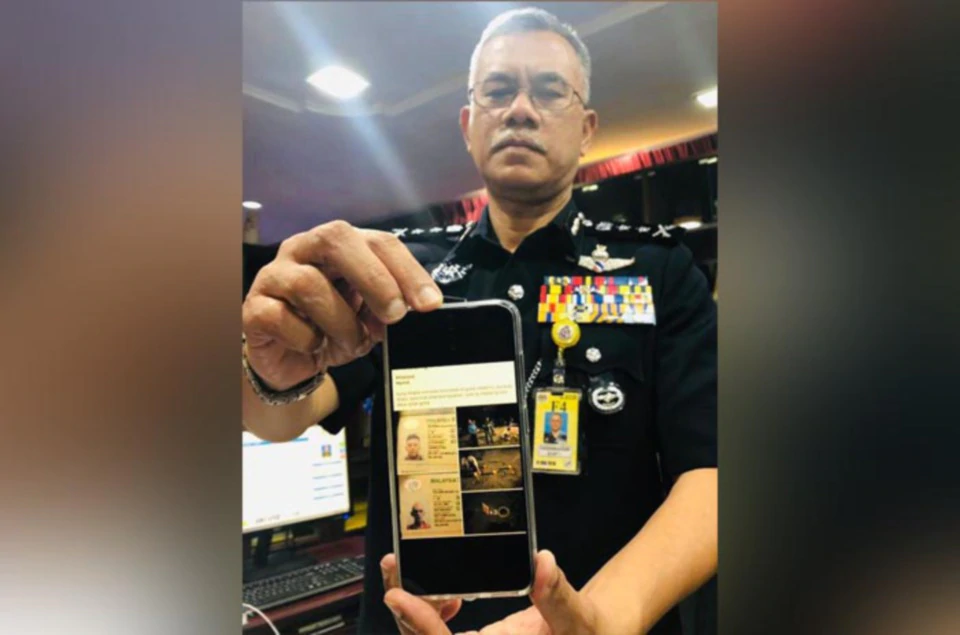

Lately too, many heart-breaking events have happened, and they led us to want to re-evaluate on how to address them and move forward. They are nation-building issues such as the national and state flags have caused upheaval in social medias. Wrong display of them, whether intentional or otherwise have led to the questioning of loyalty and patriotism. Similarly, the issue of the singing of the national anthem in Mandarin and Arabic courted controversies. These were followed by the issue of smuggling into Malaysia the asses of the late communist leader Chin Peng, whose name triggered nostalgic bad memories especially for the security forces and the victim families.

This chain of events is antagonistic to the fundamentals and political science of this country. Some might have forgotten that our country is multiracial and religious and founded on many core values that are shared by the various communities, Malays, Chinese, Indian Dayaks and Kadazandusuns.

Malaysians, especially the younger ones did not go through the suffering of during the Malayan Union 1945, the violence upheaval during the attempt of Communist Party of Malaya (1948-1989) to wrest power after Japanese surrender, the violent riot and bloodshed of the 1969 and the economic recession of the early 1980s may not be able to relate and appreciate why older generations are very sensitive to these sentimental events that brought the multi-racial, multi-ethnic Federation of Malaya and later of Malaysia.

Perhaps the major flaw of our nation’s founding policy especially after the formation of the Federation of Malaysia in 1963 was that there was not enough political will to carry through the multi-racial, multi-ethnic nation-state that was founded based on many good values such as cooperation, moderation and the spirit of give-and-take. The British territories that agreed to form Malaysia such as North Borneo (Sabah), Sarawak and Singapore were clearly bounded in many respects especially in political, economic and social but the political will to implement and honour these ‘agreements’ faded as soon as the new nation-state was in operation. After 57 years of Federation Malaysia, it is most unfortunate that some territories such as Sarawak and Sabah are still unhappy and are pushing for independence or succession, argued with the central government over the terms of oil royalties and state powers that the formers feel are being increasingly being monopolised by the centre.

History reminded us that Brunei’s last-minute refusal to stay together to realise the Federation of Malaysia was the failure to arrive at terms on oil issue between the Sultan of Brunei and Tunku Abdul Rahman. But backward, smaller and poorer nations such as Sarawak and Sabah were persuaded to join Federation Malaysia by various parties including the power that oversaw and secured the two territories.

Likewise, Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew was aware that Singapore was at the forefront of the communist threat, and that Singapore did not have enough resources to resolve social issues such as housing problem, socialist parties and powerful NGOs. Therefore, Lee Kuan Yew has no choice but to join Federation Malaysia. In many ways, Lee Kuan Yew is very grateful to Tunku Abdul Rahman. Although the island state stayed for a short while in the Federation, that period provided the breathing space to thwart communist threat and influence from settling in Singapore.

AFTER 57 YEARS

After 57 years the formation of Malaysia, what has happened to our country? Are our people really united in the name of Malaysia? Is language policy such as Bahasa Melayu as the national language helping in creating a united “Bangsa” Malaysia? Apparently, we are still separated by ethnicity and readily identifies ourselves as either Malay, Chinese, Indian, Iban or Kadazan instead of Malaysians. We are not united as Bangsa Malaysia in any real sense of the term.

The terms Bangsa Malaysia and Bahasa Malaysia are two important terms but lack of distinct definition. What is Bahasa Malaysia? Who and what do a bangsa Malaysia look like, i.e. in term of defining characteristics?

Some time in the 1980s, the term Bahasa Melayu was changed to Bahasa Malaysia. Perhaps this was done to placate non-Malays. There is no need for that as the language is still recognizably ‘Malay”. Changing the name was merely rhetoric. Bahasa Melayu and Bahasa Malaysia are two different things altogether. Bahasa Malaysia include languages spoken by Malaysian such as Mandarin, Tamil, Kadazan and Iban.

Similarly, Bangsa Malaysia has not been properly, clearly and authoritative define. What or who is a bangsa Malaysia? What do a Bangsa Malaysia display, in terms of characters, e.g. culture, language, way of lives. The term first surfaced in 1991 when Vision 2020 was launched. Till this day, there is no authoritative definition of what constitute bangsa Malaysia.

Recently I attended many seminars on nation-building where many Malay educationists also talked about the Bangsa Malaysia. There is a general agreement that they are ready to accept a larger concept like the Bangsa Malaysia, but they too are still vague on what Bangsa Malaysia is?.

In the recently conclude 2019 UMNO General Assembly, UMNO Youth Chief was reported to have spoken of the country as belonging to all races. Of course, this is obvious. Malaysia belong to those who are legally a Bangsa Malaysia, but who is he referring to as Bangsa Malaysia? The question still does not have answer yet.

In such a flux situation, there is an urgent need to formulate a new policy and to further institutionalize the Bangsa Malaysia. What form and how this can be realised may need more discourses among various segments of the society that are parts of the whole process. However, there need to emerge a political will to tackle this long-standing issue in nation-building.

Our next-door neighbour, Indonesia is undoubtedly doing a little better than us in forging their nation-state through their Pancasila ideology. We have the Rukun Negara, but this is also not really helping in pushing for the emergence of bangsa Malaysia.

The ideology of the Bangsa Malaysia must transcend racial and religious boundaries. What has been agreed in the Federal Constitution remains, but in order to move forward we must have a Bangsa Malaysia. For a start and for some time, Malaysians overseas for whatever reasons have display this bangsa Malaysia spirit, and that is when asked of their origin, they would answer “I am a Malaysian, Bangsa Malaysia”. But this spirit faded when they are closer to home. Why?

When speaking with foreigners abroad, no Malaysian would introduce the Proton car as a Malaysian Chinese car, the Petronas Twin Towers as belonging to the Malays, and Malaysia football team is a Chinese-Indian-Malay, but are proud to introduce them as Proton Malaysia, Petronas of Malaysia and the Malaysian football team respectively.

Until these fundamentals are addressed, discourses on them will oscillate from defining them based on the dominant race.

To conclude the discussions, we need to be realistic. Forever will not get concerns about Bangsa Malaysia. Bangsa Malaysia and Malaysian is two different terms. We are Malaysian. Full Stop.

Dr Al-Azharri Siddiq Kamunri. The writer’s area of study is in politics and Government and has interests on issues relating to nation-building, national security and patriotism.